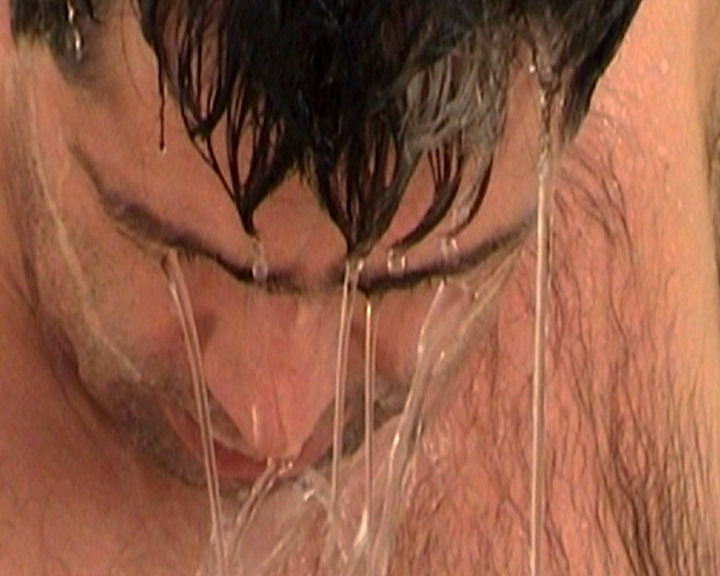

video i?, 2004, PAL video, 04:17 min., Stereo, non-Dialogue

Revisiting History

Mieke Bal

Read also the Abenteuer eines im Westen gestrandeten Migranten aus dem Mittleren Osten by Asieh Salimian

This particular history begins with Samuel Beckett, that most canonical of modernist writers who messed up any neat notion of modernism that postmodernism could reject. Poststructuralist philosopher Jacques Derrida, whose staple of favorite and inspiring writers consisted of the modernists Joyce, Kafka, Ponge, and a handful of others, not so incidentally mentions Beckett in an avowal of his incapability to write about him. The key figure of poststructuralism appears to shy away from writing about him because Beckett represents for him the essence of what is literature. I can sympathize with that sense of intimidation, of awe, in the face of greatness. Yet, such restraint is also doing the opposite of what the crucial move of GLUB was: it respects, leaving in place, and thereby, making de facto invisible what the meaning of that greatness can be for us, today. It is a way of killing the object and declaring that culture can only pay homage posthumously.

And now, Derrida is dead, and we will never know what moved him exactly.

Let me remember him by adding a little speculation to his multifaceted negative motivations. In his life-long struggle against everything that for him made structuralism the last remnant of logocentric oppression, he cannot have been insensitive to Beckett’s profoundly structuralist way of working. But, rather than being bound to pre-structuralist logocentrism in this, Beckett’s structuralism is deeply post-structuralist if we take that prefix in the complicating sense I have suggested in my introductory remarks. It is in that sense that Shahram has established a pre-posterous relationship to Beckett in his short film I? of 2004.

In this film of 4 minutes, 17 seconds, Shahram revisits for contemporary culture the conceptual nature of Becketts’only film, called FILM, starring Buster Keaton and made in 1965, two years before the actor’s death. Keaton was also a great comedian, enjoying a popular acclaim that Beckett’s difficult work would never achieve. In the typical and, by 1965 historical fashion of early cinema that had no dialogue, lots of body movement, and visual explorations of the modernist shock encounter with the city, Keaton, 40 years beyond his greatest successes of jumps and leaps around in New York, now crawls and flees from the city’s imposition of visual contact. He locks himself up in his apartment and locks all alien gazes out. He tears up every image that presents looking as a mutual act of communication, all the while never showing his face. In the final shot, and in what might be an ironic concession to the viewer hungry for realistic solutions, solutions primarily anchored in the motivation of seemingly incongruous acts, it turns out that face is distorted by the loss of an eye. In close up, this loss is literalized and made subjective as hideously distorting. The face finally revealed literalizes the trauma of the subject’s constrcutedness by the gaze of the other; Jacques Lacan was around and well by 1965.

Shahram was more interested in the conceptual nature of FILM than in any of its more modernist features. This concept includes the enlisting of a Hollywood star, of course, thus making a pre-post-modernist claim for the abolition of that boundary between popular and high culture. But the primary element of that concept is the unlikely combination of going around in the public space of the city while never revealing the face. For today, it is of crucial importance to reflect on the relationship between the individual subject whose life the constitution demands we respect, and the larger communities whose members the Western world denies that individuality. For, as I? in its intertextual relationship to FILM seeks to explore, it is not productive to remain obsessed with the individual face as long as a true Levinasian face-to-face cannot occur.

The mechanics of a conceptual exploration, abolishing the heroizing individualism that subtends Hollywood stardom along with elite notions of artistic genius, offer an opportunity to do research on identity without sentimentalizing that concept, reclaiming it from abuse in identity politics and its backlash. In this sense, I?, which we will now show you, reclaims the complex meanings of, and intricate relationships among, post-structuralism (the concept), postmodernism (the philosophy of the subject) and postcolonialism (the reclaimed, literally re-incorporated search for identity in a culturally hybrid world).

This intertextual relationship to both Beckett and Keaton, two stars of modernist as it tips over into postmodernism, is at the heart of a “new historicism” that is not an attempt to reclaim history as if poststructuralism had never happened, but instead claims a historical position for the acknowledgment of the contemporary in all historical relationships to the past. This pre-posterous historicity anchors the present in a firm bond to the past, a multiple past no less, where the past cannot be reduced to a singular cultural legacy. Shahram’s film thus juxtaposes to the past of the American West woven into Beckett’s Film by means of Keaton’s particular acting style and his by 1965 pre-posterous movements, to the past the migrant carries on his back, from the western-exploited middle East and the traces of its own popular culture in small tokens we see here and there, shimmering through their insignificance.

I? is not a remake of Film. The differences between Film and I? are important. Beckett filmed in black and white, Entekhabi in color. In spite of the passers-by in the frame, the figure in Beckett’s film is primarily alone with his identity crisis; his running, climbing and scuttling around appears to emerge from an inner need. Entekhabi is examining identity in the midst of the turmoil of the multicultural city. To Beckett’s twenty-two minutes, he substitutes a 4.17 minutes’film on a loop, increasing narrative pace while slowing down diegetic pace. The explanatory ending is gone, and replaced by a circular structure. The beginning, when the figure looks into the mirror while shaving, is buckled up to the ending, which is double. First, he enters his home through the door, then arrives there and cannot open the door. Looking into the mirror is completely different after having been a mirror to others all day long.

Those differences turn the later film into a critical commentary on the earlier one, in true postmodernist fashion. But it is also clear that this is a dialogue, not a rejection, of everything that Beckett’s film contains but keeps implicit: most importantly, the rationale of the combination of going out in a public space while hiding of the face. The later film brings out these implicit elements, pre-posterously revising the earlier work instead of treating it like a corpse ready for dissecting. This is an approach to a cultural artifact that supplements, but also constitutes, academic scholarship – indeed, revealing aspects of Beckett’s work that the written word would have a mighty hard time articulating.

Shahram’s project was also to foreground the crossing, in culture, of two systemic relationships: vertical so to speak, to other artworks from the past, here, Beckett’s and Keaton’s Film, and a horizontal one, in the present, between art and the popular culture that populates the urban space and that none of us can esoterically ignore. Both relationships already cross when Keaton, belatedly by forty years, re-enacts his past as a comic, a star of the silent film with its particular loaded movements, and his significance as the figure of the migrant going West. (Siegler 2004: 120)

Multiplying these two relationships, the need arose to continue the reflection of which I? is the result. Taking I? as a starting point for a new reflection, we have embarked here in Cleveland on a series of films where the double relationship is further elaborated. Taking up I?’s most significant allegiance to Film, the invisibility of the individual’s face remains, and foregrounded more. The face is now sometimes visible but never allows a face-to-face. Nor is there any interaction with others – a feature of I? that was the more important as the figure there was surrounded by others, a crowd even, but never engaged in interaction. In the further installments, even those surroundings disappear, replaced by cars, factories, in some, or by groups psychologically severed from the figure who appears to live in a bubble of his own, perhaps a comic-strip “glub.” [pron. Gloeb] ![]() The rhetoric of the relationship between the figure and the viewer, while continuing to be premised on the impossibility of the face-to-face, is complicated by the inscription of scopic desire.

The rhetoric of the relationship between the figure and the viewer, while continuing to be premised on the impossibility of the face-to-face, is complicated by the inscription of scopic desire.

Mieke Bal ![]() Cultural theorist and critic | Video artist

Cultural theorist and critic | Video artist

Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Professor (KNAW), 2005-2011.

Based at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA), University of Amsterdam.

The video "i?" is part of the permanent collection in the video forum of the Video Forum of the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.)

The video "i?" appeared at the following exhibitions and festivals, among others:

2013: You Are What You See — Raf Art Gallery, Tehran, Iran (solo show)

2015: “i?” — Visual Cultures (Lecture), Goldsmiths University of London, United Kingdom

2009': Das Bild des Fremden in Deutschland und Frankreich’ — Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM), Berlin, Germany

2009': bedün´ ? onvän´ 3 — Short video pieces reflecting on social & gender issues in Iran — Barbican Centre, Silk Street, London, UK

2009': Video art selection — Video Art program, curated by Sabine Schütze, Preview Berlin The Emerging Art Fair , Berlin, Germany

2009': The Third Guangzhou Triennial — Guangdong Museum of Art, China

2008: PROYECTO MONOLOGS — Laboratorio Global de Monologos y Video — curator Elisa Eliash, Rome, Italy

2008: IDEAL.LOOP — Espace Croisé, Roubaix Cedex 1, France

2008: LOOP’08 Festival “SELECTED #3, A source for videoart lovers” — The sixth videoart festival LOOP’08, Barcelona, Spain (catalogue)

2007: Kunstfilmtag — Kuenstlerverein Malkasten, Duesseldorf, Germany (catalogue)

2007: 100 Tage = 100 Videos, GL Strand, Copenhagen, Denmark (catalogue)

2007: TRUNK07, THE NORDIC ART VIDEO FESTIVAL — CinemaRegina, Östersund, Sweden

2007: LED-Wall, Zeithaus, VW Autostadt, Wolfsburg, Germany

2007: Optica, International Festival of Video Art — GIjón-Asturias, Spai

2006: Labyrinth X - zu Rassismus und Ausgrenzung — Nikolaikirche, Rostock, Germany

2006: Beckett & Company, panel discussion and artist talk — Tate Modern, London, UK

2005: Exhibition of the 10 winning videos of the festival FIAV.05 — Metrònom, Barcelona

2004: “i?” — PLAY Gallery for Still and Motion Pictures, Berlin (solo show)